What does leadership look like when the system forgets to care? In this post, I walk through Kafkaesque corridors of bureaucratic silence, only to find an unexpected teacher in a public park—one who leads without title, teaches without mandate, and answers a call no one officially made. This is a story about the politics of care, about those who take responsibility when no one else will.

Prelude: Walking into the Aleph

There are moments in life that lodge themselves into your very being, reverberating across your ways of knowing, living, and leading. In the triad of perceived, conceived, and lived experience, some events fracture time itself—before and after take on new meanings. What follows is not just a recollection but a return. A descent into one such moment, drawn from what I now call My Aleph—a point of convergence where multiple realities collided, revealing the cruelty of systemic failure and the stubborn hope that sometimes emerges from its ruins.

Entering the Labyrinth

It was August 2007, when I assumed charge as Principal of a public school in Islamabad, handpicked through a rigorous federal commission process. Like many new leaders, I arrived with a well-packed toolbox which had in it, a bundle of policy guidelines; mantra of vision, mission and values; a pack of strategies to bring change; management techniques; operational and procedural know-hows; theories of motivation; planning tools for goal setting and achievement; tactics of using audio-visual aids to enhance outcomes; and I believed that my tool box was well equipped. It was not.

The day I crossed the barbed-wire boundaries and rigorous security checks, I was jolted into a very different kind of terrain. What met me was not a school in need of reform but a structure barely holding itself together. Physical ruin. Pedagogical fatigue. Isolation. And above all, abandonment.

The school was a forgotten outpost and was infamous in the teaching community as the hardest station in terms of access and quality. No public transportation access and cumbersome security checks are required each day, due to the potential security risk in the grim national security setting in the post 9/11 war on terror, which isolates it from other parts of the city. It was tucked in the shadow of a military headquarters, physically barricaded and metaphorically disconnected from any enabling system. Teachers were temporary, reluctant, and weary. Students came from families surviving on daily wages, housework, and informal labour. These were the children whose education was never anyone’s priority. Each morning, the teachers prayed for the final bell; each evening, I went home carrying the weight of defeat.

I started zealously and with persuasive communication with top management, elucidating the appalling conditions of my school, seeking attention and resources. Unfortunately and un-expectantly, for one or the other bureaucratic reason, each of my requests for additional resources and change frameworks met a similar fate of delayed promises, eventually leading to no action.

Every official request, though backed by evidence, passion, or even desperation, was met with procedural deferral. Promises slid into silence. Files moved, but nothing moved forward. Kafka’s corridors of waiting became mine. My leadership, once imagined as purposeful, became an exercise in persistence against faceless walls. With a heavy heart, I was on the verge of giving up.

An Unexpected Aperture

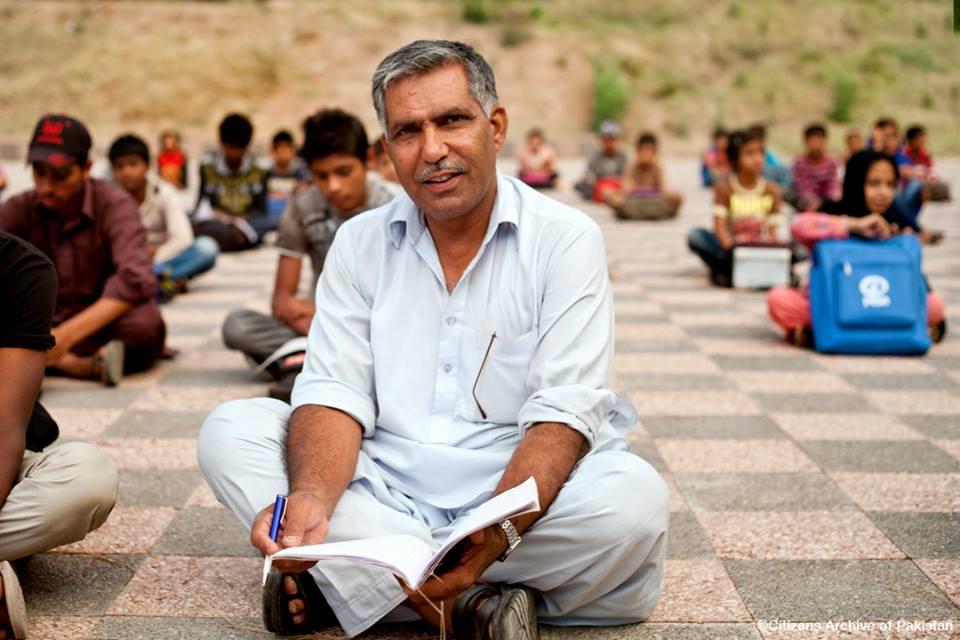

I was beheld with a sight most worthy of sights and witnessed a happening amongst the most valued of all happenings in my life. It was when I was on my way to school that I had to take a detour due to an ongoing road work and had to go through unfamiliar streets in one of the posh sectors of Islamabad. After taking a few turns, I saw a large group of children sitting in a semi-circle on a bare concrete floor of the park, under the overcast sky and amidst frost-laden autumn leaves. What caught my attention took me was that despite the harsh weather, they were focused on a middle-aged man standing in front with a make-shift blackboard, and instinctively I had to stop. After parking my car and upon entry into the park, a closer look at the semi-circle revealed the appearance of a busy classroom with open school bags. It was an assemblage of children of different age groups, multiple ethnicities (as clear from their appearances) and both genders. The only striking commonality was their poverty, acutely obvious in their insufficient winter clothing and visible malnourished physiques.

The man with the blackboard seemed like their teacher. As I approached nearer, I became the focus of attention for the whole group. Little embarrassed and feeling like an intruder, I hesitantly stopped. As if sensing my discomfort, the man left what he was doing and approached me with an assuring smile. He was Muhammad Ayub, in his late forties and a volunteer teacher, as he called himself. By profession, a firefighter and a government employee in the city’s emergency services, he had set up this school for children from disadvantaged strata of urban society in Islamabad. Trapped in the vicious cycle of multiple deprivations, they were the children denied their basic human right to get an education.

To answer my curiosit,y he told me that for the last twenty-two years he had been teaching children as young as five years left by their parents to fend for themselves and driven into child labour, or ones as old as 12 years dropped out (or I would rather say pushed out) of schools after being ridiculed for their empty virtual bag (Thomson, 2002). Not being trained as a teacher, yet he had been successfully transferring knowledge in basic literacy, numeracy and necessary conduct in a school; thus had been preparing them for mainstream education or simply adding literacy as an additional skill to their repertoire.

While listening to him, I shuddered with painful thought that perhaps they would never hear about those numerous national and international treaties for education as the basic human right, pledged by governments in majestic edifices of public offices. And here was Master Ayub (as children lovingly called him), oblivious of these treaties and public education policies long on rhetoric and short on resolute actions, and responding to the call of human responsibility.

He had been fighting against the “unfairness of precluding poor children from school”, NOT “to protect them from working too early” (Tomasevski, 2003, p. xiii), but in a quest to give them a better view of their chances and possibilities in this world. Respecting individual entrepreneurial energies, he used to teach young workers in the evenings and protect private lives; he teaches older girls in their homes, all in the hope of providing them with means for a secure and productive tomorrow.

“It is on the day that we can conceive of a different state of affairs that a new light falls on our troubles and our suffering and that we decide that these are unbearable.”

—Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980)

Where Bureaucracy Ends, Responsibility Begins

That morning, I stood haunted by a quiet question: Why is it that those with no obligation often carry the deepest sense of responsibility? While state apparatuses perfected the art of procedural evasion, here was a man who had no reporting officer, no allocated budget, no official recognition—and yet, every morning, he showed up. In Kafka’s world, where answers are never clear, and authority remains elusive, Ayub was an anomaly: someone who acted without being asked, who responded without being accountable to power, only to conscience.

His care was not bureaucratised. It was human. It did not flow from organisational imperatives but from ethical urgency. And in his refusal to wait for permission, he enacted a form of leadership that stood in quiet but powerful indictment of every strategy that had failed children like his. He gave me the tools my toolbox needed.

Learning to Lead Otherwise

Master Ayub’s classroom taught me more about education than any theory or professional development session ever had. It shattered my assumptions about where leadership resides. Perhaps true leadership begins when the ‘tools’ run out—when one is disoriented, stripped of systems, and left with nothing but the trembling insistence that something must be done. In the bureaucratic maze of educational policy, where responsibility is always someone else’s, Master Ayub had found a way to act. I was going to find mine.

That day, something within me re-aligned. I stopped seeking ready-made models and began listening to the faint, fragile voices of those who teach and lead without recognition. I let go of my desire to perfect the broken system and instead began learning how to navigate it with care, with defiance, and with fidelity to those it routinely forgets.

Afterword: Tracing the Labyrinth with Care

There are no heroic conclusions here. Only a reminder that within the Kafkaesque mazes of our institutions, there are still people who draw classrooms into the dust, who refuse to let children disappear, and who remind us, those of us in positions of power, that being answerable is not the same as being responsible.

Master Ayub taught without a title. But his was a leadership no policy ever accounted for, and no metric could capture.

Sometimes, the most transformative politics of care emerge from those who are unanswerable—and yet still answer.

References

Tomasevsky, K. (2003). Education Denied – Cost and Remedies. London and New York: Zed Books.

Thomson, P. (2002). Schooling the Rust Belt Kids – Making the Difference in Changing Times. Australia: Allen & Unwin.

Leave a comment